Our research

There are >750,000 described species of insects, by far the largest grouping of animals on the planet, and they are critically important to human society in both harmful (vectors of disease, agricultural pests) and beneficial (pollinators) ways. Insects use an astonishing variety of anatomical and molecular specializations to sense and interact with their environment, providing input that guide decisions and behaviors essential for survival: Is that a predator? What do I eat? Whom should I court? Where should I lay eggs?

The biological diversity of insects offers an opportunity to understand the genetic and genomic underpinnings of behavioral and physiological adaptation. Comparative genomics and the adaptation of genome editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 to new species allow us to directly probe specific genes and neural circuits that are not found and cannot be studied in traditional model systems. Our laboratory takes an integrative approach to understand insect behavior and physiology, primarily focusing on the arboviral vector mosquito Aedes aegypti.

Behavior

Insects exhibit a staggering array of complex and specialized adaptive behaviors. Our work primarily focuses on the arboviral vector mosquito Aedes aegypti, which feeds on human blood and lays eggs in water. These behaviors are deadly adaptations that drive disease transmission and range adaptability.

Genomics and genetics

We use genomic and genetic techniques to identify specialized genes and neural circuits underlying behavior. With a comparative approach across diverse strains and species, we hope to understand how an organism’s genome can encode the capability for adaptive behaviors.

Sensory biology

Behavior is driven by sensory cues (for example: smell, taste, vision, touch), which are perceived with specialized molecular receptors expressed in sensory neurons. We use an array of genetic and neurobiological approaches to understand the logic of sensory coding in mosquitoes and other insects.

Mosquito behavior

Larval and pupal moquitoes develop in aquatic environments, and, thus, gravid adult mosquitoes must choose appropriate places to lay eggs to maximize the survival and fitness of their offspring. This means identifying bodies of water that are large enough to survive evaporation, are free of predators, and are comprised of water of the appropriate salinity and osmotic pressure. *Aedes aegypti* mosquitoes directly contact liquid water to evaluate its chemical composition before laying eggs singly above the waterline, and will reject even moderately brackish saltwater. Their ability to exploit small containers of freshwater associated with human habitation as breeding sites, like discarded tires, drinking water containers, or clogged gutters, helps ensure that the next generation will have easy access to their preferred source of blood. One major goal of the lab is to understand the cues that *Ae. aegypti* and other mosquito species use to evaluate egg-laying sites and the behavioral adaptations that allow different strains and species of mosquito to exploit specific breeding sites. In particular, we are interested in the coordinated changes in sensory systems and larval physiology associated with freshwater and saltwater specialist mosquitoes.

Genomics and genetics

Genetics is a powerful tool for understanding biology, and understanding the genome of an organism is essential for guiding and performing comprehensive genetic analyses. The genome of the Ae. aegypti mosquito is large and repetitive, and the previously available reference assembly was highly fragmented and incomplete which hampered the analysis and identification of genes and gene families critically involved in mosquito behavior. During my postdoctoral work, I was heavily involved in an international effort to re-sequence, re-assemble, and re-annotate the genome of a laboratory strain of Ae. aegypti, resulting in a dramatically improved chromosome-scale assembly and geneset annotation that now forms the basis for studies of many aspects of mosquito biology. In addition, we profiled gene expression in male and female brain and sensory tissues to identify candidate genes involved in host-seeking and egg-laying and gene networks regulated by blood-feeding state. Together, these foundational resources support comparative analyses of insect genomes and enable direct and mechanistic studies of all aspects of mosquito biology.

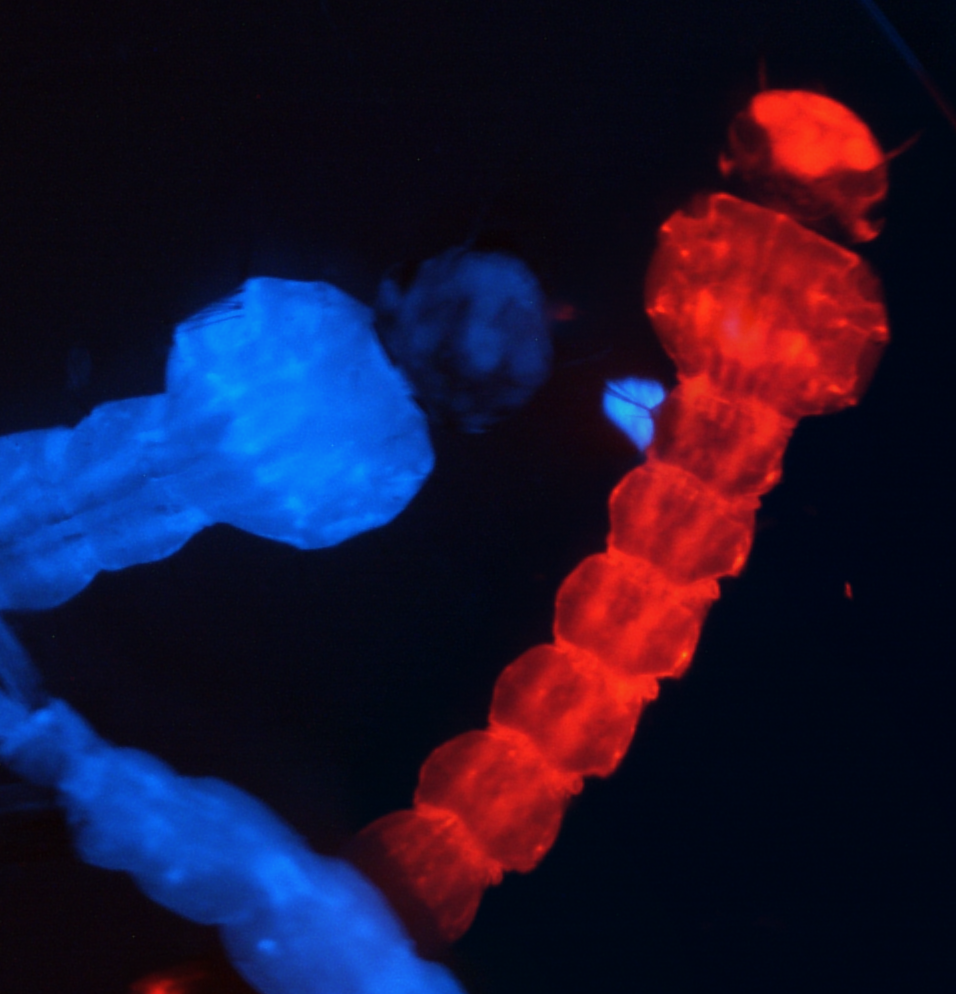

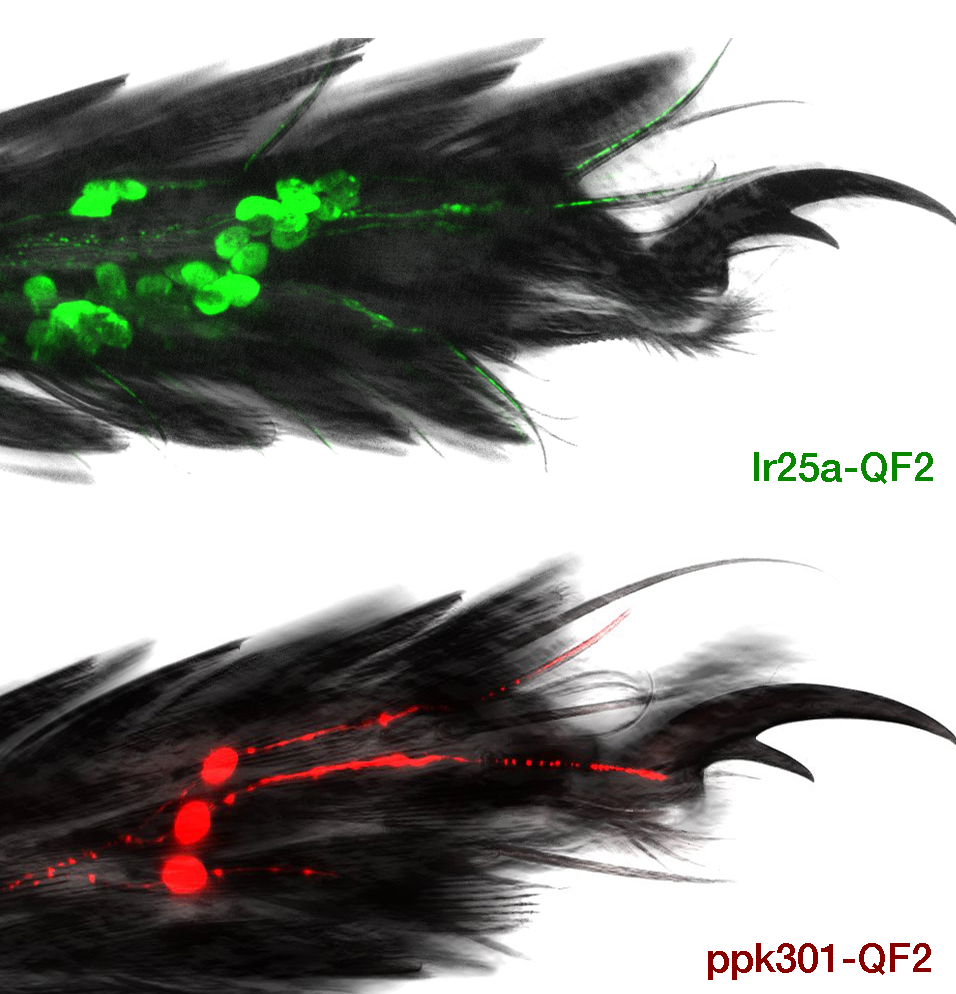

To directly test the role of specific genetic loci in biological processes, we develop and adapt genome-editing techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 to make precise and specific manipulations to the genome of a Ae. aegypti and other non-traditional model insects. These manipulations allow us to study the effects of removing specific genes on insect behavior and physiology, as well as to ‘knock-in’ transgenes, such as driver lines that recapitulate the spatial and temporal expression pattern of endogenous genes. When combined with transgenic reporters, these targeted drivers allow us to visualize molecularly-defined neural circuits, image their activity in response to behaviorally-relevant sensory cues, and artificially manipulate their activity to study their causal role in generating behavior. The lab continues to focus on breaking new ground in insect genetics by developing tools and strategies for directly linking genes, cells, and behavior in an integrative fashion and in behaviorally-relevant contexts across a diverse array of organisms.

Sensory biology

Understanding the cues, genes, and circuits used to shape egg-laying in Ae. aegypti will identify novel receptors and cell types and help describe the logic of how and where mosquito sensory systems process and integrate multiple sensory cues to generate adaptive behavior. Our philosophy is that it is critical to study mosquito biology directly in the mosquito: in addition to furthering our understanding of sensory systems at the comparative level, the receptors and cells identified as part of these studies represent new targets for mosquito control.

Ae. aegypti lay eggs in freshwater and avoid laying eggs in saltwater, and actively sample a potential egg-laying site with sensory appendages including their legs and proboscis. We set out to understand the molecular and neural circuit basis of this behavior, focusing on the pickpocket family of genes that encode ion channel subunits. We identified one gene, ppk301, that when mutated, caused severe delays in egg-laying, even when presented with normally-preferred freshwater. Using calcium imaging, we identified a population of sensory neurons that express ppk301 and show ppk301-dependent neural activity in response to water but, unexpectedly, also respond to salt in a ppk301-independent fashion. This suggests that ppk301 and ppk301-expressing sensory neurons represent a key instructive signal for exploiting suitable freshwater egg-laying sites, but that ppk301-independent high-salt pathway(s) operate to prevent egg-laying under high-salt conditions.